Start With a Simple Question

A good place to activate our work to improve our cities is with solid questions. Questions can be big or small, or even a series of nested questions. They can be broad or specific, with a long-term or short-term focus. It can guide something as large as a city-wide project, a smaller project, or a small gathering.

We create projects and initiatives to improve our cities, whatever the subject: active transportation, biodiversity, reducing red-tape at city hall, a community garden, a plan for the city …

The process of making an initiative come alive in the city is composed of innumerable conversations: a nestwork of conversations. A solid, simple question with an invitation into purposeful exploration is at the heart of initiatives that successfully involve a variety of city perspectives. That question guides the entire project, both the bigness of the endeavour and all the possibilities that may come with it, and the specifics of the smaller conversations embedded the larger process.

“A solid, simple question with an invitation into purposeful exploration is at the heart of initiatives that successfully involve a variety of city perspectives.”

For both the project and specific conversations along the way, a good question:

Clarifies the purpose of the project or a meeting.

Provides focus for the project over time and each meeting.

Provides boundaries to limit the scope of the project and the scope of conversation at each meeting.

Conveys values about the project that and the work in each meeting.

Invites more questions for deeper exploration.

Allows expansion of the conversation into a broad and deep range of ways to explore the question.

Guides research for the project, and the work of people working on the project.

Guides the design for conversation processes for the whole project and at each stage of the project.

My clients and I don’t always have an easy time finding the right question, but they are worth the effort because they make the difference between being muddled and confused and intentional and clear in our work (often with many others) to improve our cities. Each time, we know we’ve landed the question for the project when it feels simple. It is somehow both specific and big and we sense that it will be relevant right to the end of the project, not limited to a specific stage or phase or aspect of a project.

Two recent examples of solid questions that support city planning initiatives are identified below: Edmonton’s Evolving Infill action plan, and Edmonton’s draft City Plan.

How do we welcome more people and homes into our older neighbourhoods?

This question served as the “spine” for all the conversations that created an action plan for Edmonton’s city government to encourage infill development: the Infill Roadmap. Layers of conversation took place, starting with generating ideas, then organizing and sorting the ideas, followed by evaluating and choosing the right actions in Edmonton.

Engage a range of intelligence and expertise

The question was put to four key perspectives in the city system: citizens, community organizations, the business community, and various pockets of local government. In the idea-generation stage early in the engagement process, these perspectives worked separately, then gathered to integrate their ideas. Their mission was to explore the big question and identify specific actions that are appropriate for city government to take. The result: the Infill Roadmap.

The question led to a concrete action plan for city government

The question served to guide every conversation about the Infill Roadmap: among and between citizens, builders and developers, community organizations and across and within city hall, all recorded in the “What We Heard” Report. The question also guided the technical studies that informed the action plan and the final iteration of the Infill Roadmap.

The question focused engagement, research and technical reports

Most important, the question allowed everyone working on the action plan, including citizens and neighbourhood organizations, developers and builders, community advocacy organizations and our local governments, to focus on the desired impacts of action. A boundary was set: the results of the actions were identified. The purpose of the initiative and why were were working on it, were clear.

The question allowed citizens, builders, community and city hall to identify actions with impact

When the purpose of a project is clear we enable the city to move in a chosen direction.

What choices do we need to make to be a healthy, urban and climate resilient city in a prosperous region?

The question that drove the creation of Edmonton’s draft City Plan (at public hearing September 14-16, 2020) focused on identifying choices and making choices. The big question drove the project through each stage of its creation—both with the writers of the plan in city hall, and within each stage of engaging conversations across the city. This question enabled a conscious conversation about choices and trade-offs.

A conversation about choices and trade-offs: Who do we choose to be?

The conversations started with values and themes of ideas to identify city building outcomes and “big city moves” to shape the city. Next, the conversations focused on articulating the specific choices we have to make—and making them. Once having made choices, the policies to guide city government action were crafted. When we name our choices we enable choice-making.

“When we name our choices we enable choice-making.”

Through the five big city moves, Edmonton chooses to:

Be greener as we grow and choose to protect and enhance our land, air, water and biodiversity.

Be a rebuildable city and choose to plan for flexibility and imagination to it can adapt to our changing future.

Be a community of communities and choose to make city life welcoming with community districts with access through all forms of transportation.

Be inclusive and compassionate and choose to make efforts to improve equity, end poverty, eliminate racism and make clear progress towards Truth and Reconciliation. (We choose to look out for one another.)

Catalyze and converge and choose to be an entrepreneurial hub around which investment, innovation, technology and talent will gather.

To accomplish the five big city moves 24 city building outcomes were identified with 70 policy intentions and 350 policy directions to attain those outcomes.

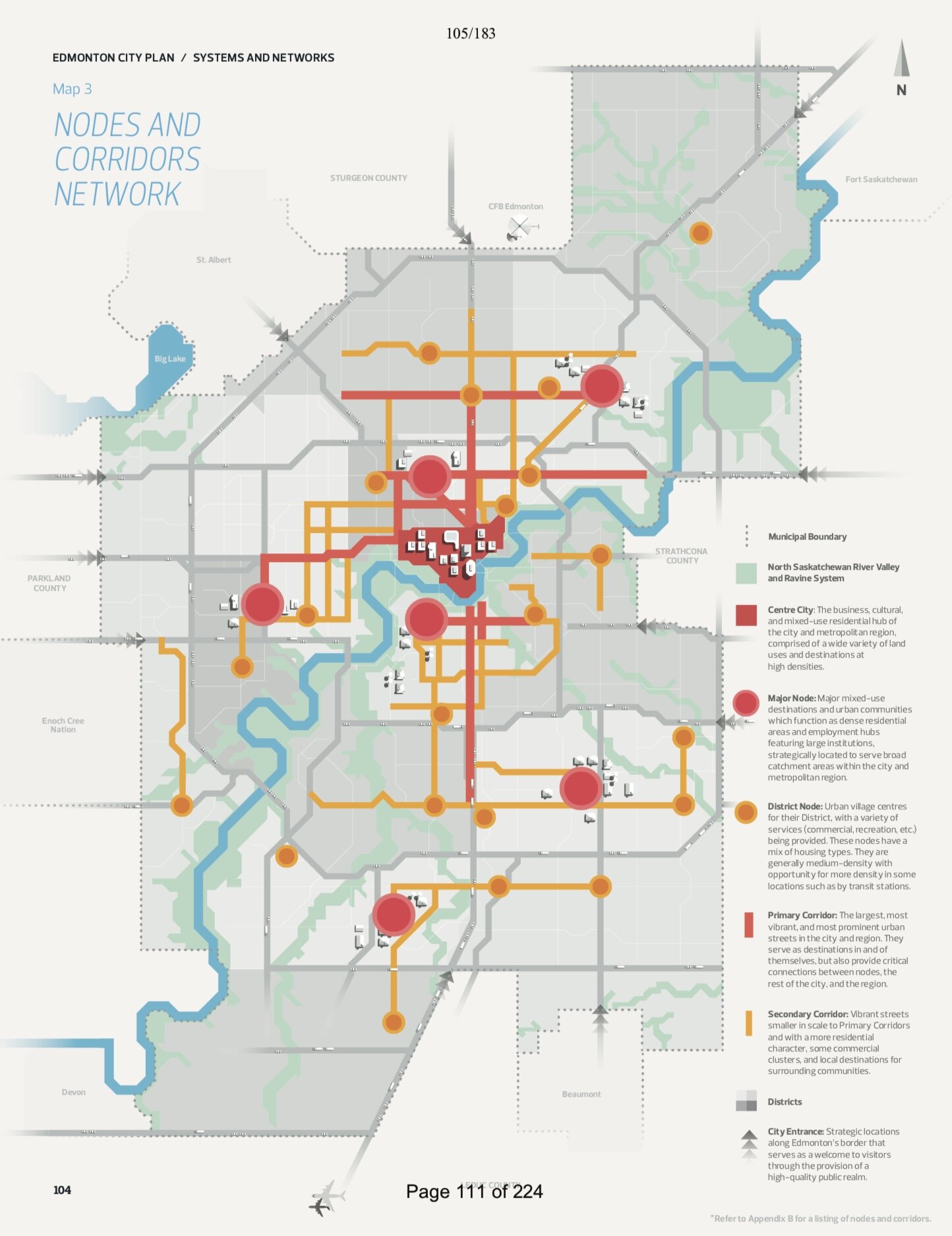

In terms of how we spatially organize ourselves, the plan identifies choices about how to invest in our city infrastructure. Edmonton chooses to create a:

Network of districts of neighbourhoods where everyone meets their daily needs as much as possible locally (and making it easier and more enjoyable to walk, bike and take transit).

Network of nodes and corridors to create strategic development opportunities city-wide, not just at transit centres.

Network of natural and human ecological elements: the green and blue network (land and water) that supports the river valley and ravine system, a habitat greenway, an urban greenway, and major recreational parks.

Network of non-residential opportunities to support existing industrial, commercial and institutional areas and generate new opportunities.

Choice: What kind of city are we?

Choice: a built form that nurtures community, investment, mobility equity and climate resilience

Choice: support ecological connectivity and biodiversity

The extensive technical work behind the scenes to model development scenarios also focused on the question; the scenarios modelled the consequences of different questions. The question that served as the “spine” for the project expanded from a question for public engagement to a question that was embedded in the research and in the final plan itself. (In fact, as I watch the public hearing, the question has been cited by members of the public as they speak to city council!)

Tips to find your question

A warning: the exploration to find “the question” can be long and arduous. Trust that you will find that simple question that will energize your work. Trust that once the simple question is found the work will flow from that question.

Here are some questions help you find the question that can best support your city project:

What is the purpose of our project? What do we hope to achieve in the short-, medium- and long-term?

What are the specific issues we see the project can focus on? How does the focus of each stage of the project change?

What boundaries will be helpful to enable the project? What is the project not about?

What are the values that are important to this work?

What questions are swirling around the project? Which ones are bigger or out of scope, which ones fit within? Which is the magic question to guide our work?

REFLECTION:

What questions, implicit or explicit, are guiding your work?

What questions, implicit or explicit, are guiding work of others?