A Firestorm of Emotion

I stepped out of my spacious and fluid life a year ago when I decided to work long days, with my schedule determined for me (and no time for writing), with the Municipality of Jasper. I've been pitching in, helping Jasper rebuild after the 2024 Jasper Wildfire Complex incinerated a third of the town and setting up the municipality's first Urban Design and Standards department (think planning and development).

Jasper is 12 months into its recovery. While extremely lucky that the 32,722 hectare (80,869 acre) wildfire that swept the valley did not engulf the whole town, or the key infrastructure that would make recovery more difficult (the water systems, hospital and schools were saved), it is arduous work to clean up after devastating loss, then more work to rebuild what was lost.

Please donate to Jasper’s ongoing recover with a donation to the Jasper Community Team Society.

Jasper on August 14, 2024

While residents and my colleagues have been cleaning up town and preparing for rebuilding, the more difficult work is the community's experience of anger, frustration, grief and sadness. It would be easier if the fire hadn't happened, the clean-up had been faster, or there had been no permits, rules or regulations. It would be easier if the fire hadn't happened. But it did.

No one who lost their home or business asked to lose their belongings or livelihood, or to have an unexpected multi-year project to rebuild. No one wanted to leave town because their home was lost, live in a hotel, bunk with family or friends, or in makeshift housing for years. No one wanted to reimagine their livelihood without a building--or a third of the town. No one wanted their work to disappear or change completely. It would be easier if the fire hadn't happened. But it did.

The number fifty

A few months ago, a town council member asked me, "There's an idea floating around town that only fifty permits for people to rebuild will be issued this year—is this true?" There is no limit to the number of permits issued to rebuild, so I replied, "The number of permits issued will be the number of permits applied for."

I've been pondering how information spreads—especially when not based in fact. I don't need to know where or how the idea of a cap of fifty permits started. I'm curious about what motivates people to spread ideas that incite frustration and anger.

Here's what I notice about myself: it is hard to look at things as they are and not as I want them to be. To avoid looking at things as they are, I will tell myself a story that distracts me from my deeper feelings.

“It is hard to look at things are they are and not as I want them to be.”

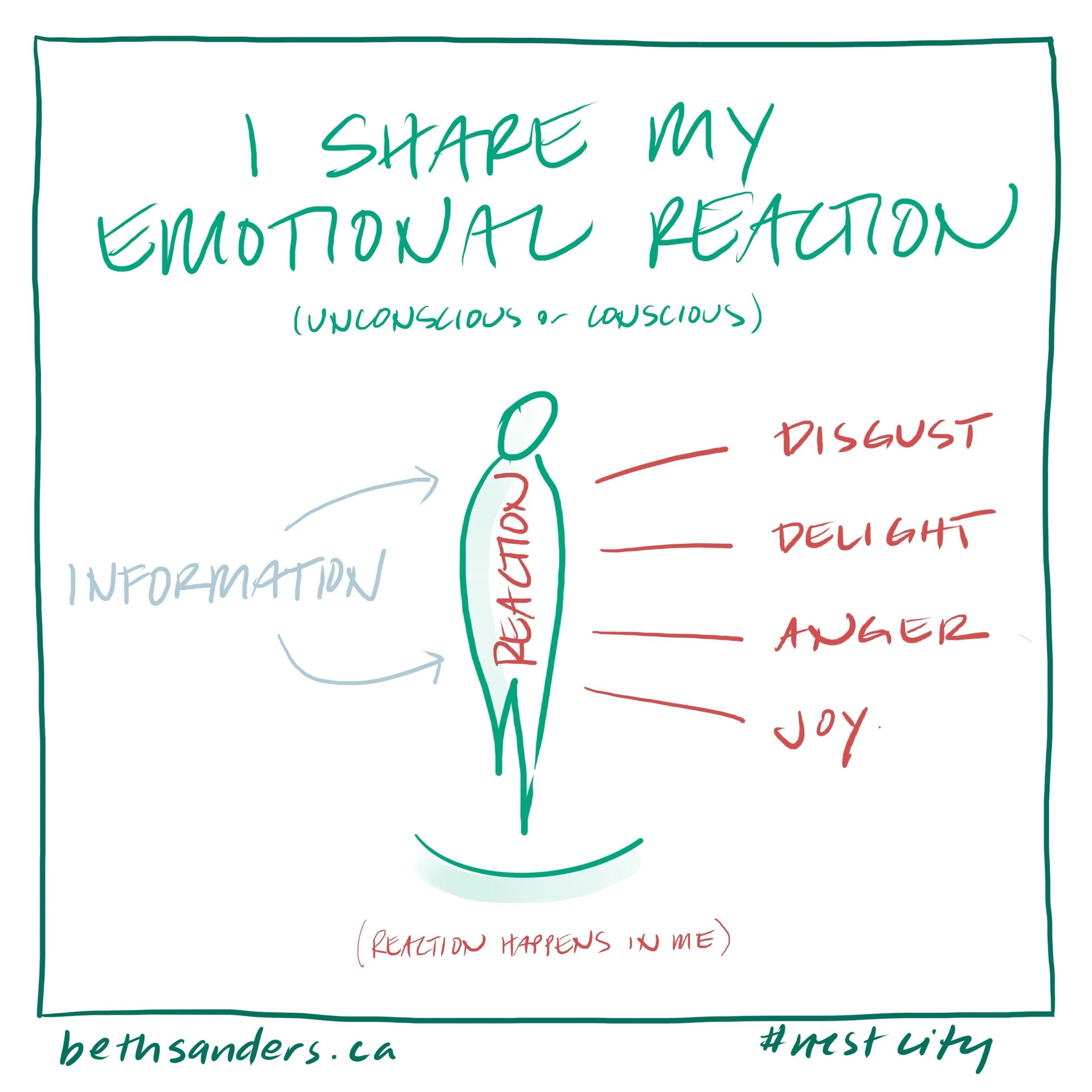

If I'm not vigilant, this is what I do (and maybe you do it too?) I hear information and react with like, dislike, love, or disgust. If I'm not careful, I will integrate that information into my understanding of the world based on my reaction. Without interrogating the information, I assume that the information is accurate because liking or disliking the information is what I believe. I believe what I want to believe, then share information to convince people to share my belief.

I resist assessing if the information is accurate to feel good about my opinion. For example: "Look at what so-and-so did! This proves they are a selfish, horrible person who only looks out for themselves." Or: This proves that they are a great person!" I share and spread my emotional reaction: disgust, delight, anger or joy.

What I want to believe impacts what I hear and allow myself to hear. Avoiding information I don't want to hear means I avoid feeling something I don't want to feel. In contrast, I pause to recognize that while I don't like, or do like, a person's decisions, I don't know if the stories floating around are true. How could I find out? What do I stand to gain by believing without questioning?

“What I want to believe has an impact on what I hear—and what I allow myself to hear.”

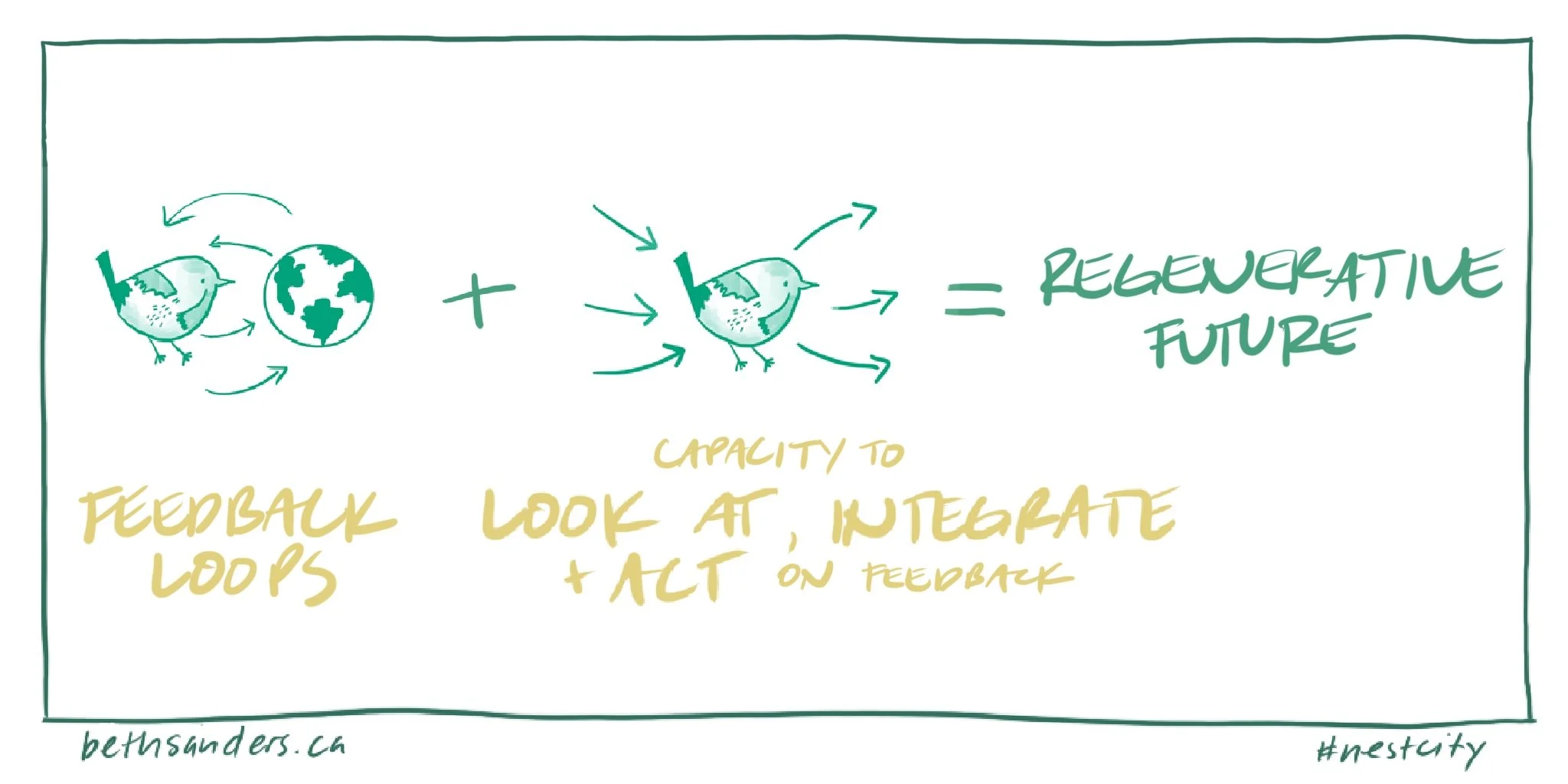

I feel sad about the number fifty story because it highlights how misinformation and disinformation hinder Jasper's recovery. Someone, somewhere, chose to invent a story and share it. Others chose to believe it and share it. It's a stark example of how any community blocks itself from a healthier version of itself.

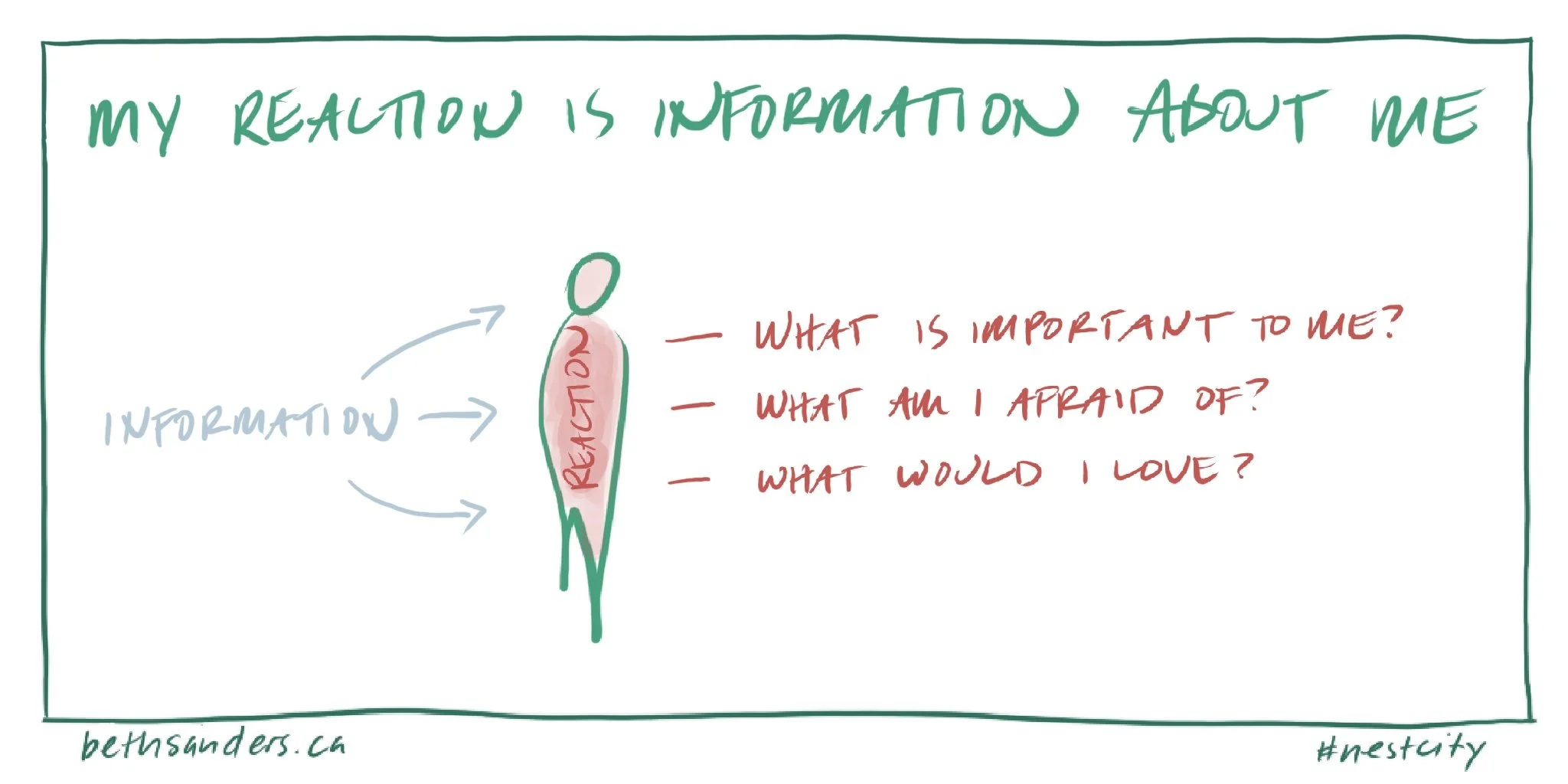

Instead of wallowing in the anxiety I feel, I choose to look at the situation and explore how my reaction has essential information for me with three questions:

What is important to me?

What am I afraid of?

What would I love?

Accurate information is important to me. As I work in Jasper, ensuring that my colleagues and I share verifiable information about rebuilding is important. I value clear and effective communication. I value integrity — the alignment of actions and words. I value choosing actions in the short term that will serve Jasper well into the near and long term. Our work will not be perfect, so it's important to acknowledge mistakes as opportunities to improve our work.

I am afraid of Jasper's collapse. I am afraid of misinformation and disinformation and the wilful disregard for looking a challenging situation in the eye. Climate change and wildfires are real, not fake. The delightful collection of people who lived here before the evacuation on July 22, 2024, will never be the same, even if we rebuild the town to look the same. The work to rebuild Jasper is hard emotional work. I am afraid of pretending that our work is not emotional.

I love the idea of considering our emotional reactions as a window into vital information about ourselves. It's not about noticing that I like or dislike something, but WHY I do. I ask, "Why is that 'why' important? My emotional reactions present opportunities to identify unacknowledged feelings and desires, revealing choices.

Feelings are vital information

My feelings are useful information about how I feel, not about whether or not "that thing" I am reacting to is real or true or not. A situation, or information that comes my way, and my reaction are not the same, and it's not helpful to confuse the two.

If I dare to interrogate myself, my emotional reactions provide profound insights about choices to better live my life in alignment with what matters to me.

A year ago, when I was negotiating terms to begin working with the Municipality of Jasper, I was responding to a long-standing desire to work with one community (rather than many as a consultant), to lead a fantastic team (rather than work with different people every week), and to spend more time in Jasper.

The wildfire changed the nature of the work my new employer and I were imagining for me. I hadn't yet signed the offer letter, so I could have walked away. Like many across Canada and the world, I was horrified by the emerging news of destruction from Jasper. A town was being destroyed, and a job was going up in smoke (pun intended).

A year ago, five questions helped me tease out my reaction:

How am I reacting to the information about Jasper's destruction? I am desperately sad for Jasper, a special place in my heart, and worried about an exciting professional opportunity slipping away.

What story am I telling myself about Jasper's destruction and the job? I didn't know how much of Jasper was destroyed in the early days. I had moments of anxiety: "The professional opportunity is gone. I have to find another way to invigorate my work." I also had moments of calm: "My future colleagues in Jasper have more significant matters to attend to now. They'll get in touch when it makes sense, so my work is to be patient."

How does the story I believe shape my reaction? When I tell myself the opportunity is gone, I feel anxious. When I tell myself, "They'll get in touch when the time is right for them," I feel more calm. With the latter, I look for factual information and start to think about what the early days post-disaster would look like for planning and development people. I reach out to say, "I'm still IN."

How does the story I believe encourage me to dismiss information that doesn't fit, or welcome new information? When looking for the facts and giving myself space to react to that information with horror and distress, I could accept information I didn't want to believe. When my "I'm still IN" message was acknowledged with "Glad to hear you're IN. I'll call on Friday," I had a moment of panic on Friday when the call did not come. One story: "They're not interested in me. This opportunity is disappearing." Another story: "Political officials are in town and they have a lot to do. It is reasonable to expect a call when it works for them. I must practice patience because Jasper's response is not about me." I choose my emotional reaction.

What do I choose to share with others? When I share information, I distinguish between verified factual information about destruction, recovery and rebuilding and my emotional reaction. Emotions are information, but not facts.

There is a question behind these questions: How is my emotional reaction guiding my choices? My feelings always provide accurate information about me, not an assessment of whether what sparks my reaction is true.

Emotions reveal beliefs

My emotional reactions reveal the thinking behind my choices. I could have walked away from the intensity of post-disaster work a year ago and refused the call. I could have been sad that the work I thought I would be doing was gone. My self-talk would have been: "This is too much, I'm not capable, I'm not interested."

In contrast, an alternate response is two-fold: sadness about the disaster and excitement about a surprise professional opportunity. As news emerged about damage to the town, a close friend said to me, "It's like Jasper knew it was going to need you." Instead of dismissing this new focus for my work, I sat back in wonder about a magical confluence of my interests: community planning and supporting communities as they grapple with choices to resolve community challenges.

In the end, the choice was about believing in my capacity to shift my work far more dramatically than I had imagined. I'm not up for the task. Or, I'd love to see where this task takes me.

To Jasper, I said yes.

I continue to say yes.

Reflection

What emotional reaction are you having right now to a situation?

Why is that situation important to you?

What are you afraid of, relative to this situation?

What would you love to be different?

What unacknowledged emotions are you spreading?

Emotional accuracy: What words would help you pinpoint your emotional reaction to the situation?